Last updated on May 5, 2021

R. O. Parke Loyd, Arizona State University

The Sun isn’t the only star to produce stellar flares. On April 21, 2021, a team of astronomers published new research describing the brightest flare ever measured from Proxima Centauri in ultraviolet light. To learn about this extraordinary event – and what it might mean for any life on the planets orbiting Earth’s closest neighboring star – The Conversation spoke with Parke Loyd, an astrophysicist at Arizona State University and co-author of the paper. Excerpts from our conversation are below and have been edited for length and clarity.

Why were you looking at Proxima Centauri?

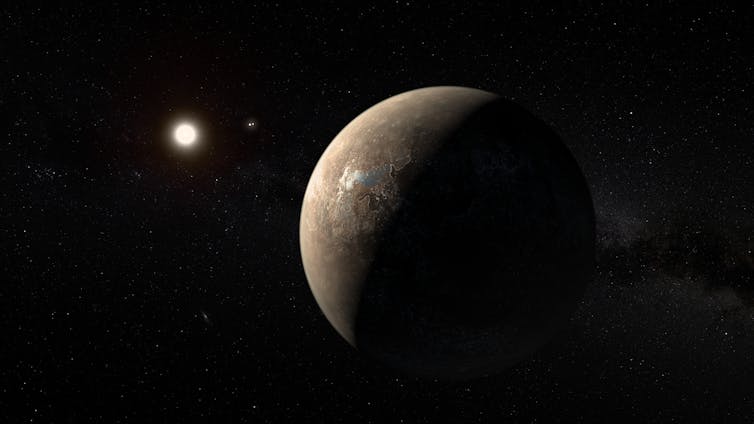

Proxima Centauri is the closest star to this solar system. A couple of years ago, a team discovered that there is a planet – called Proxima b – orbiting the star. It’s just a little bit bigger than Earth, it’s probably rocky and it is in what is called the habitable zone, or the Goldilocks zone. This means that Proxima b is about the right distance from the star so that it could have liquid water on its surface.

But this star system differs from the Sun in a pretty key way. Proxima Centauri is a small star called a red dwarf – it’s around 15% of the radius of our Sun, and it’s substantially cooler. So Proxima b, in order for it to be in that Goldilocks zone, actually is a lot closer to Proxima Centauri than Earth is to the Sun.

You might think that a smaller star would be a tamer star, but that’s actually not the case at all – red dwarfs produce stellar flares a lot more frequently than the Sun does. So Proxima b, the closest planet in another solar system with a chance for having life, is subject to space weather that is a lot more violent than the space weather in Earth’s solar system.

What did you find?

In 2018, my colleague Meredith MacGregor discovered flashes of light coming from Proxima Centauri that looked very different from solar flares. She was using a telescope that detects light at millimeter wavelengths to monitor Proxima Centauri and saw a big of flash of light in this wavelength. Astronomers had never seen a stellar flare in millimeter wavelengths of light.

My colleagues and I wanted to learn more about these unusual brightenings in the millimeter light coming from the star and see whether they were actually flares or some other phenomenon. We used nine telescopes on Earth, as well as a satellite observatory, to get the longest set of observations – about two days’ worth – of Proxima Centauri with the most wavelength coverage that had ever been obtained.

Immediately we discovered a really strong flare. The ultraviolet light of the star increased by over 10,000 times in just a fraction of a second. If humans could see ultraviolet light, it would be like being blinded by the flash of a camera. Proxima Centauri got bright really fast. This increase lasted for only a couple of seconds, and then there was a gradual decline.

This discovery confirmed that indeed, these weird millimeter emissions are flares.

What does that mean for chances of life on the planet?

Astronomers are actively exploring this question at the moment because it can kind of go in either direction. When you hear ultraviolet radiation, you’re probably thinking about the fact that people wear sunscreen to try to protect ourselves from ultraviolet radiation here on Earth. Ultraviolet radiation can damage proteins and DNA in human cells, and this results in sunburns and can cause cancer. That would potentially be true for life on another planet as well.

On the flip side, messing with the chemistry of biological molecules can have its advantages – it could help spark life on another planet. Even though it might be a more challenging environment for life to sustain itself, it might be a better environment for life to be generated to begin with.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

But the thing that astronomers and astrobiologists are most concerned about is that every time one of these huge flares occurs, it basically erodes away a bit of the atmosphere of any planets orbiting that star – including this potentially Earth-like planet. And if you don’t have an atmosphere left on your planet, then you definitely have a pretty hostile environment to life – there would be huge amounts of radiation, massive temperature fluctuations and little or no air to breathe. It’s not that life would be impossible, but having the surface of a planet basically directly exposed to space would be an environment totally different than anything on Earth.

Is there any atmosphere left on Proxima b?

That’s anybody’s guess at the moment. The fact that these flares are happening doesn’t bode well for that atmosphere being intact – especially if they’re associated with explosions of plasma like what happens on the Sun. But that’s why we’re doing this work. We hope the folks who build models of planetary atmospheres can take what our team has learned about these flares and try to figure out the odds for an atmosphere being sustained on this planet.

R. O. Parke Loyd, Post-Doctoral Researcher in Astrophysics, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.