Last updated on August 23, 2020

After terrorists slammed a plane into the Pentagon on 9/11, ambulances rushed scores of the injured to community hospitals, but only three of the patients were taken to specialized trauma wards. The reason: The hospitals and ambulances had no real-time information-sharing system.

Nineteen years later, there is still no national data network that enables the health system to respond effectively to disasters and disease outbreaks. Many doctors and nurses must fill out paper forms on COVID-19 cases and available beds and fax them to public health agencies, causing critical delays in care and hampering the effort to track and block the spread of the coronavirus.

“We need to be thinking long and hard about making improvements in the data-reporting system so the response to the next epidemic is a little less painful,” said Dr. Dan Hanfling, a vice president at In-Q-Tel, a nonprofit that helps the federal government solve technology problems in health care and other areas. “And there will be another one.”

There are signs the COVID-19 pandemic has created momentum to modernize the nation’s creaky, fragmented public health data system, in which nearly 3,000 local, state and federal health departments set their own reporting rules and vary greatly in their ability to send and receive data electronically.

Sutter Health and UC Davis Health, along with nearly 30 other provider organizations around the country, recently launched a collaborative effort to speed and improve the sharing of clinical data on individual COVID cases with public health departments.

But even that platform, which contains information about patients’ diagnoses and response to treatments, doesn’t yet include data on the availability of hospital beds, intensive care units or supplies needed for a seamless pandemic response.

The federal government spent nearly $40 billion over the past decade to equip hospitals and physicians’ offices with electronic health record systems for improving treatment of individual patients. But no comparable effort has emerged to build an effective system for quickly moving information on infectious disease from providers to public health agencies.

In March, Congress approved $500 million over 10 years to modernize the public health data infrastructure. But the amount falls far short of what’s needed to update data systems and train staff at local and state health departments, said Brian Dixon, director of public health informatics at the Regenstrief Institute in Indianapolis.

The congressional allocation is half the annual amount proposed under last year’s bipartisan Saving Lives Through Better Data Act, which did not pass, and much less than the $4.5 billion Public Health Infrastructure Fund proposed last year by public health leaders.

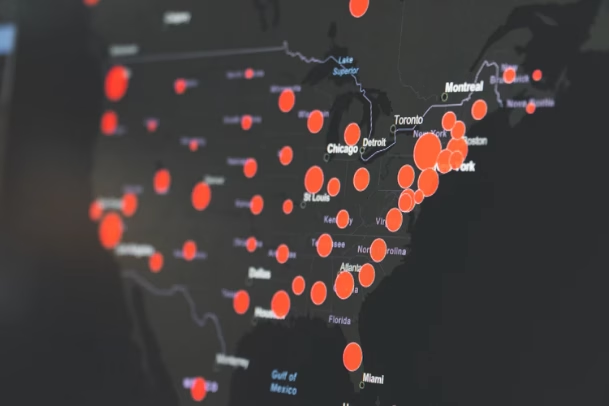

“The data are moving slower than the disease,” said Janet Hamilton, executive director of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. “We need a way to get that information electronically and seamlessly to public health agencies so we can do investigations, quarantine people and identify hot spots and risk groups in real time, not two weeks later.”

The impact of these data failures is felt around the country. The director of the California Department of Public Health, Dr. Sonia Angell, was forced out Aug. 9 after a malfunction in the state’s data system left out up to 300,000 COVID-19 test results, undercutting the accuracy of its case count.

Other advanced countries have done a better job of rapidly and accurately tracking COVID-19 cases and medical resources while doing contact tracing and quarantining those who test positive. In France, physicians’ offices report patient symptoms to a central agency every day. That’s an advantage of having a national health care system.

“If someone in France sneezes, they learn about it in Paris,” said Dr. Chris Lehmann, clinical informatics director at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Coronavirus cases reported to U.S. public health departments are often missing patients’ addresses and phone numbers, which are needed to trace their contacts, Hamilton said. Lab test results often lack information on patients’ races or ethnicities, which could help authorities understand demographic disparities in transmission and response to the virus.

Last month, the Trump administration abruptly ordered hospitals to report all COVID-19 data to a private vendor hired by the Department of Health and Human Services rather than to the long-established reporting system run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The administration said the switch would help the White House coronavirus task force better allocate scarce supplies.

The shift disrupted, at least temporarily, the flow of critical information needed to track COVID-19 outbreaks and allocate resources, public health officials said. They worried the move looked political in nature and could dampen public confidence in the accuracy of the data.

An HHS spokesperson said the transition had improved and sped up hospital reporting. Experts had various opinions on the matter but agreed that the new system doesn’t fix problems with the old CDC system that contributed to this country’s slow and ineffective response to COVID-19.

“While I think it’s an exceptionally bad idea to take the CDC out of it, the bottom line is the way CDC presented the data wasn’t all that useful,” said Dr. George Rutherford, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California-San Francisco.

The new HHS system lacks data from nursing homes, which is needed to ensure safe care for COVID patients after discharge from the hospital, said Dr. Lissy Hu, CEO of CarePort Health, which coordinates care between hospitals and post-acute facilities.

Some observers hope the pandemic will persuade the health care industry to push faster toward its goal of smoother data exchange through computer systems that can easily talk to one another — an objective that has met with only partial success after more than a decade of effort.

The case reporting system launched by Sutter Health and its partners sends clinical information from each coronavirus patient’s electronic health record to public health agencies in all 50 states. The Digital Bridge platform also allows the agencies for the first time to send helpful treatment information back to doctors and nurses. About 20 other health systems are preparing to join the 30 partners in the system, and major digital health record vendors like Epic and Allscripts have added the reporting capacity to their software.

Sutter hopes to get state and county officials to let the health system stop sending data manually, which would save its clinicians time they need for treating patients, said Dr. Steven Lane, Sutter’s clinical informatics director for interoperability.

The platform could be key in implementing COVID-19 vaccination around the country, said Dr. Andrew Wiesenthal, a managing director at Deloitte Consulting who spearheaded the development of Digital Bridge.

“You’d want a registry of everyone immunized, you’d want to hear if that person developed COVID anyway, then you’d want to know about subsequent symptoms,” he said. “You can only do that well if you have an effective data system for surveillance and reporting.”

The key is to get all the health care players — providers, insurers, EHR vendors and public health agencies — to collaborate and share data, rather than hoarding it for their own financial or organizational benefit, Wiesenthal said.

“One would hope we will use this crisis as an opportunity to fix a long-standing problem,” said John Auerbach, CEO of Trust for America’s Health. “But I worry this will follow the historical pattern of throwing a lot of money at a problem during a crisis, then cutting back after. There’s a tendency to think short term.”

This article was originally published by Kaiser Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.