Last updated on July 15, 2020

Xiaoping Du, University of Illinois at Chicago

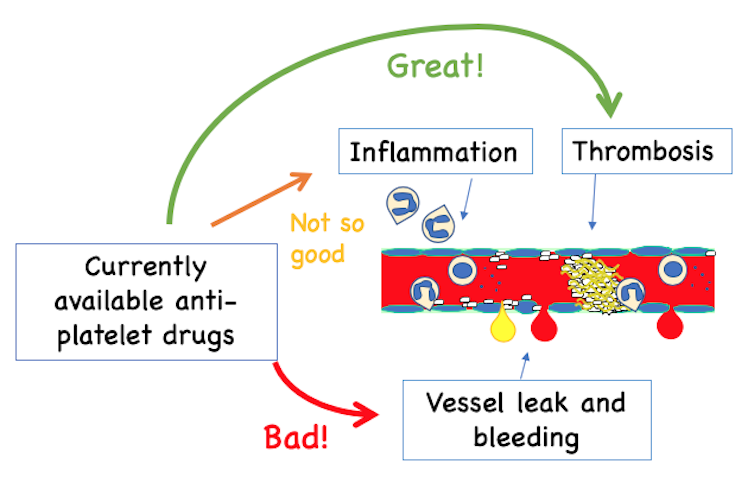

Clots obstruct blood vessels and can be deadly. They cause heart attack, stroke and are also a major problem in severe cases of COVID-19 patients. Treating clots with available drugs, however, can cause blood vessel leaking and bleeding, which can also be deadly in some circumstances.

To address this problem, my colleagues and I have engineered a new anti-platelet drug designed to prevent vessel-blocking blood clots without causing bleeding. This drug shows promise in treating heart attack and may also be useful for other severe conditions caused by clots, such as stroke and COVID-19 patients with clots and blood vessel leaks.

As a scientist studying the biology of blood cells and vessels, I am particularly interested in understanding how platelets – a kind of blood cells important in clotting – participate in the formation of clots to stop bleeding or obstructing blood vessels. Our results are published in Science Translational Medicine and show how this drug can effectively treats heart attack in mice.

How heart attack damages the heart

Heart attack and other disease conditions caused by clots cause more deaths than any other diseases in the world. In the U.S. alone, there are about 800,000 heart attack cases each year. Less than half of the heart attack patients are able to be saved by doctors. More than 30% of heart attack survivors suffer from debilitating heart failure, developed from injuries during heart attack.

Heart attack can cause heart failure and death in two different ways. First, the clots block the blood flow to the heart and cause a lack of oxygen, resulting in damage to the heart muscles. This is called ischemic injury.

This is typically treated by a procedure called angioplasty, which reopens the clogged blood vessel; and a stent, which prevents the reopened artery from collapsing. The patient is also given anti-platelet drugs to prevent the artery from clotting again.

However, fresh blood flowing into the damaged heart tissue following successful treatment can trigger inflammation, which happens when white blood cells attack the damaged heart tissues, and cause leaks and clots in small blood vessels in the heart, resulting in further damage. This is so-called reperfusion injury, which can increase the chance of heart failure and can be deadly.

A new anti-platelet drug

Current anti-platelet medications, such as Plavix, prevent blood clotting that cause heart attack and stroke but also disrupt platelets’ ability to stop bleeding if a blood vessel becomes leaky. The current drugs have only mild effects in preventing inflammation.

This new drug prevents clots but allows platelets to patch the wound, which all other available anti-platelet drugs have failed to do. This is potentially ideal for patients who need to be treated for clotting, but also need surgery or have leaky blood vessels.

The invention of this new drug is based on our previous discovery that a protein responsible for platelets to stick to the blood vessel wall to patch the wound can also bind to another protein inside a platelet to send a signal that triggers the formation of a much larger, tougher and more dangerous clot. When our team interferes with the binding of these two proteins, the formation of vessel-obstructing clots is prevented, but the ability of platelets to stick to the vessel wall to stop bleeding is preserved.

We designed a peptide, which is a small fragment of a protein, and packed it into tiny nano-particles that enter the platelets and block the signal. This new drug candidate can prevent the formation of blood vessel-obstructing clots without causing blood vessel leaking and bleeding.

Testing impact of new drug on a heart attack

Because the new anti-platelet drug we are developing does not cause blood vessel leaks, I and my colleagues were hopeful that this new drug would help limit reperfusion injury and reduce the chance of heart failure and deaths.

We tested our hypothesis in mice. After obstructing the mouse coronary artery to cause a heart attack, a researcher injected our new drug before reopening the artery to mimic treatment in humans.

Mice that did not receive the drug had clots in the small vessels and inflammation in the heart. These mice had severe damage to their heart muscles which reduced the ability of the heart to pump blood. Also, most of these mice died in a week. The new drug treatment inhibited clotting, reduced inflammation, reduced damage to the heart and improved the ability of their hearts to pump blood. And, most of the mice survived.

At this time, the new drug has not been tested in humans and is formulated to be injected into veins for it to work, which limits its use outside hospital. Hopefully, pills for daily uses can be developed in the future if trials in humans are successful.

It is very exciting for me to see such promising results in the lab, and we are now performing further preclinical work in order to bring this new drug to the clinical trials for treating heart attack in humans.

This new drug should have therapeutic potential not only for treating heart attack. But I hope that it is also effective for other clotting-induced disease conditions such as stroke. In the brain, both clotting and bleeding can cause stroke, and both are life-threatening. Thus, an anti-platelet drug that does not cause bleeding is a lot safer.

In addition, this type of drugs may theoretically also have potential for treating severe cases of COVID-19, in which patients suffers from severe oxygen deprivation, inflammation, blood vessel leak and clotting.

Xiaoping Du, Professor of Pharmacology, University of Illinois at Chicago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.